You know something? This was the first time I had ever seen her handwriting - her floppy, amateurish signature, her scribbled kisses. How was it possible? I mean, I know we’re not the most expressive of couples, but all the same. God damn, two years on and off, and not even a note? God damn.

- John Self, from Martin Amis’s novel ‘Money,’ 1984

I can’t recognize the handwriting of my best friend. I see it only annually, on my birthday card. I know how she texts, though, how her abbreviations bunch and run up against each other when she’s excited or overwhelmed. I know she rarely uses emojis, save for when she diplomatically deploys an off-color heart. Omg don’t worry at all I completely get it 💜

At the life drawing studio, I attend classes with a loose coalition of regulars. We sit and draw the same model, but we produce very different drawings. It is easy to tell the drawings of Ron from the drawings of Charles from the drawings of Zak. Ron draws big and narrow, rendering slender faces and long limbs in dark lines. Charles draws without picking up his pen, stalling over eyes and mouths. Zak tends to reiterate, a hip or breast emerging from a sea-current of line.

I recognize their handwriting, too; Ron elongates his A’s and E’s as he might a model’s face. The handwriting of the others, too, seem natural extensions of their drawing.

I do not know how they text. I do not text them. I don’t know their birthdays, or their partners, or where they like to go out. But when someone leaves behind a drawing, I know whose it is. And when they write me a note, they don’t have to sign it.

Handwriting, like drawing, is a marshalling of factors within and beyond an individual’s control. More settled factors like education, upbringing and taste compete with transitory ones like dexterity, tools, and mood.

My handwriting, like my drawing, is unmistakably mine. There are debts to acknowledge, of course, people I’ve been influenced by or outright stolen from: the bubbly handwriting of my much-idolized older cousins, the double-story lower-case ‘a’ of my third-grade teacher.

But there are other debts, too, ones that I’ve forgotten or unconsciously adopted. Graphology, the analysis of handwriting, is most concerned with these unconscious gestures: slant, size, spacing, and regularity. Graphologists go beyond using handwriting to identify an individual, and use handwriting to identify an individual’s personality and psychological disposition.

Camillo Baldi, a 17th century Italian philosophy professor, is widely regarded to be the father of graphology. Baldi did not mean to invent graphology. He meant to write a manual on letter-writing, a popular topic amongst the upwardly-mobile merchant class of the time (a true Renaissance man, Baldi also wrote volumes on philosophy, physiognomy, and duelling, or how to avoid duelling.) In this particular volume, though, he included a crucial aside which many graphologists point to as the genesis of the field, claiming such traits as prudence, avarice, and propensity to contract cholera could all be told by a man’s hand.

Wow! What can we now parse from text messages? Whether or not a man has an Android.

Graphology developed over the succeeding centuries as a fringe method of inquiry, alongside other more established disciplines like psychology and medicine. It became a kind of tea-leaf-divination for learned men, kept alive mostly in the circles of eccentric French clergymen.

Borne up by the tidal wave of psychoanalysis, graphology had a brief popular revival from the late 19th into the mid-20th century. Intending to try my hand, I picked up A Manual of Graphology, written by the Austrian poet, writer, and psychologist Eric Singer in the 1940s. Deeply influenced by the works of Freud, Singer devotes much of the book to seeking manifestations of an individual’s id and ego in the patterns of his handwriting.

Singer’s Manual is a dense and ranging text, littered with disclaimers that seem to undercut its usefulness. “No general tendency in handwriting, and no single sign, is by itself adequate to judge a man’s character,” Singer writes in the first chapter. Fig leaf in place, Singer barrels ahead to make some pretty sweeping claims. Let’s take this example, culled from the third chapter:

“Small handwriting… can mean lack of self-confidence, inferiority complexes, resignation, obedience, but also realism, the faculty of observation, accuracy, reliability, clever husbanding of personal resources, intentional understatement and distaste for boasting of every kind. It may also mean physical or mental short-sightedness, sophistication, intolerance, hypochondria and melancholy.” (Singer, 40.)

Graphology, like psychoanalysis or astrology, takes small differences and extrapolates larger ones. It is useful only so far as we are able to pick and choose the parts of broader generalizations that can help us to better understand ourselves. My handwriting is small: this is clearly evidence of my clever husbandry of personal resources and unusual sophistication (not to mention my distaste for boasting of every kind.)

Singer died in 1969. He lived twenty years after graphology was largely discredited by a series of scientific trials conducted in the forties and fifties. After his death, his wife collected and published his major works, Graphology for Everyman, The Graphologist’s Alphabet, and A Handwriting Quiz Book, as the hefty A Manual of Graphology. Despite being shunned by the scientific community, the manual was a commercial success.

The demands of optimization have largely eliminated hand-writing from professional spaces, and relegated it to those most sentimental of social occasions. This makes hand-writing something of a statement in itself. It can be, among other things, a statement of tradition (calligraphed invitations), a statement of romance (love letters), or a statement against the total encroachment of the digital (paper day planners.)

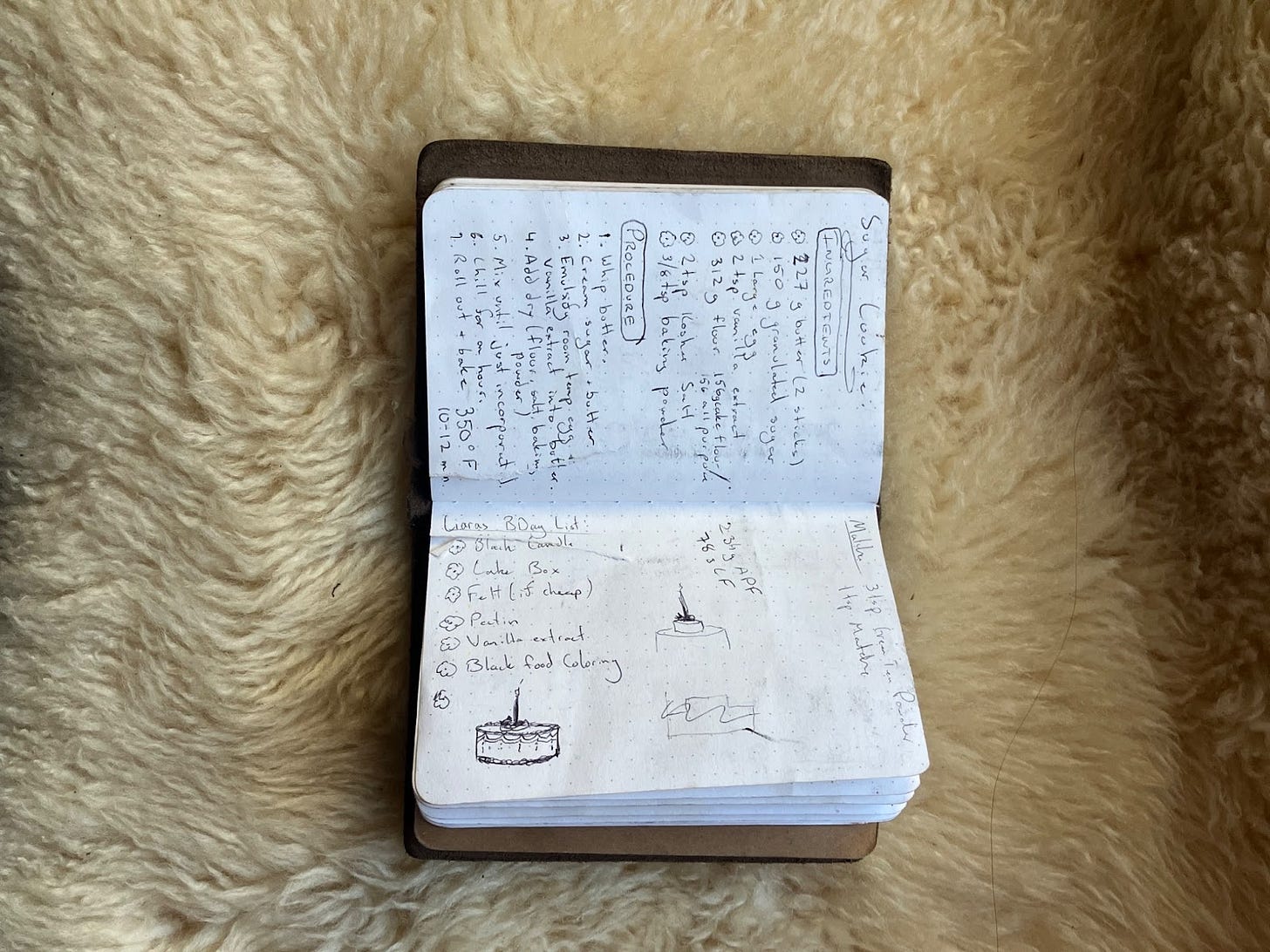

My friend Robin is a gifted pastry chef. She carefully transcribes all of her recipes in a leather-bound notebook, whether she has developed them, inherited them, or found them online. It’s a habit she picked up from her grandmother.

Robin’s handwriting does not lead me to any conclusions about her psychological state. But in the act of hand-writing, she establishes that she cares deeply about her craft, and she establishes herself within a familial and professional lineage. Handwriting is a statement of our individuality, and can also be a statement of our participation in broader traditions.

Thanks for reading! In next week’s blog, we’ll talk about an Italian scholar who changed our understanding of art attribution with a graphological method, inspiring Freud and Arthur Conan Doyle.

Another interesting and enlightening column and a bonus recipe to boot! Thank you to Robin, can’t wait to try making your sugar cookies.